Gen Z kids struggle with mental health across Southern NM

From COVID to gun violence fears, factors fueling mental health decline are wide-ranging

Juan Corral, Southern New Mexico Journalism Collaborative

LAS CRUCES - Southern New Mexico’s kids are experiencing a mental health crisis.

Along with a trend seen nationwide, Southern New Mexico’s current middle and high schoolers — who together comprise the younger members of Gen Z — are experiencing steeper mental health challenges than kids before them. And they’re living out a seeming paradox. On one hand, youth overall are engaging in less risky behaviors — like drinking and smoking — than earlier generations. But they’re seeing higher rates of anxiety, depression and suicidal behavior. One Las Cruces-based mental health counselor said an overall lack of motivation is a big problem in schools.

The youngest cohort of Gen Z, the generation whose ages now are about 12 to 27, had the unfortunate distinction of entering their teen years and growing up amid the COVID-19 pandemic, a chaotic time that, for many reasons, didn’t help their existing mental health challenges. Students were stuck, for months, at in-home learning and lacked the face-to-face social connections and structural support that in-person school offers. Local experts said the ripple effects on kids’ mental health are still being felt.

Sherri Rhoten, executive director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness Southern New Mexico, said since the pandemic, “we have seen a major increase in the number of services needed in school districts for the individuals with special education.” The nonprofit organization advocates for people affected by mental health conditions by emphasizing lived experiences.

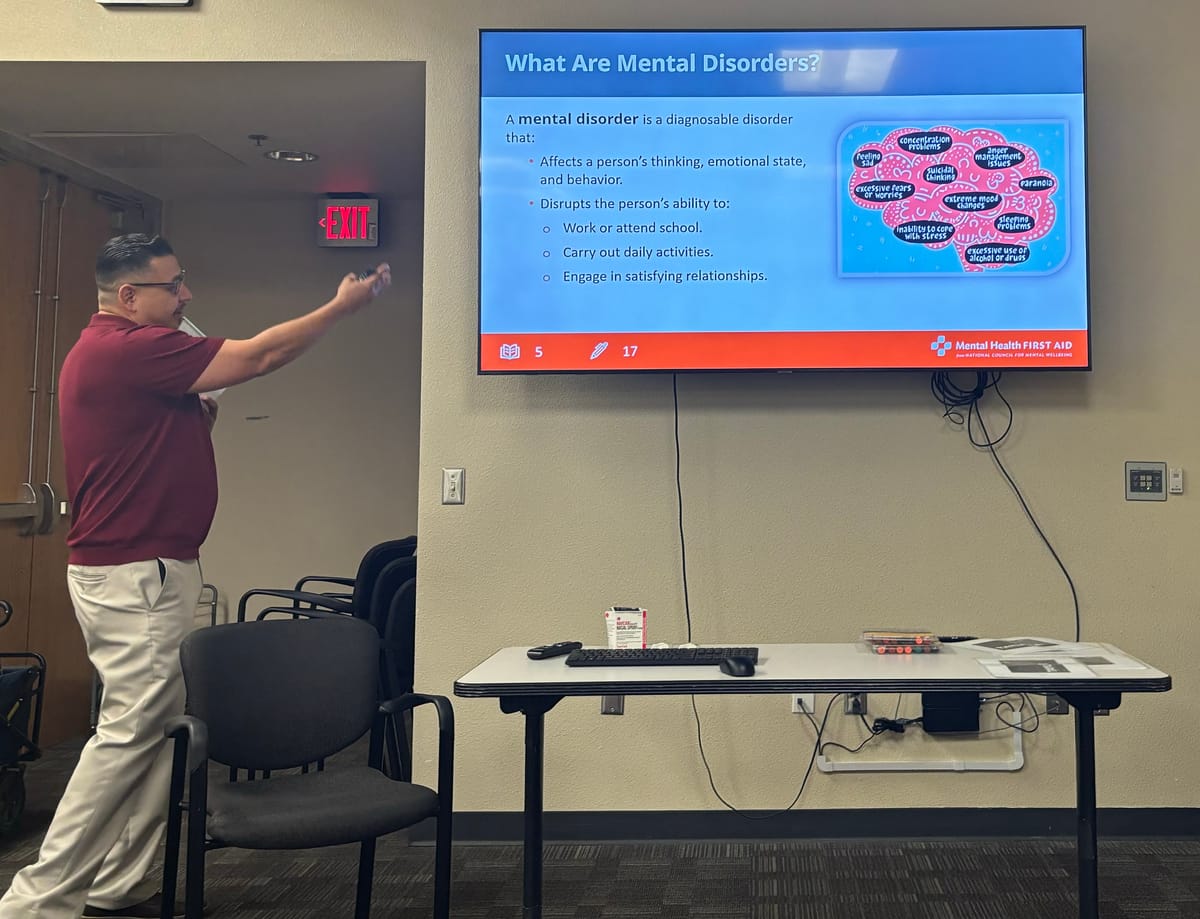

“There is a lot more struggle with the students getting their accommodations,” Rhoten said. “We have been advocating for a lot more families than we have in the past.” Despite the challenges, efforts are underway to help youth. A national crisis hotline – 988 – is geared to help kids, as well as adults. In Doña Ana County, adults who want to learn more about kids’ mental health issues – and find out about resources – can attend so-called “mental health first aid” trainings. At Organ Mountain High School in Las Cruces, students hosted an awareness campaign recently to help their peers counter thoughts of suicide.

Nearly all youth in survey expressed concerns

A 2023 nationwide poll of Gen Zers found that roughly 9 out of 10 youth experienced some form of mental health challenge, such as feeling overwhelmed, stressed, lonely or anxious. The survey, carried out by The Harris Poll on behalf of Blue Shield of California, asked youth ages 14 to 25 a series of mental health questions and had a margin of error of plus or minus 3.5 percentage points.

Even before COVID, several factors seem to be driving a trend of worsening youth mental health. The rise of social media platforms, like TikTok, over the past decade and their accessibility to kids via smartphones and tablets has raised major concerns among experts. This access has some positives, such as for education and entertainment, but it also enables cyberbullying, a worry that’s deepened more recently because the advent of AI can make that toxic practice easier to carry out and more damaging than before.

Lara Walter, social worker at Organ Mountain High School in Las Cruces, said many of the students she sees experience bullying in-person and online. She said popular apps also seem to contribute to children being depressed or questioning their self-worth. Some of the culprits?

“TikTok, Instagram, Twitch, and Discord,” she said in a recent interview with the Southern New Mexico Journalism Collaborative.

Last year, 77% of high school students reported using social media at least several times a day, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There’s a growing body of evidence about the harms of social media on children and teens, according to a 2023 U.S. Surgeon General’s Report. Up to 95 percent of teens use social media with about one-third reporting they use it almost constantly, per the report. But there are still gaps in the body of academic research about the possible negative effects, making it difficult to draw comprehensive conclusions, according to the report.

Nonprofit fields more calls for help

In Luna County alone, Rhoten said, NAMI Southern New Mexico had contact with 274 parents on school-related issues in the month of August, just as the school year got underway.

“Whether it be bullying or special education issues – we have seen a huge increase this year,” she said. “In the past, I might have helped with eight to nine IEPs a year, and I have already done more than that, and the school year just started.”

An IEP is an Individualized Education Program, a school’s plan designed to help students with special needs or a disability, such as a mental health condition.

In 2022, the Deming Public Schools, which serves Luna County, hired an outside agency to boost its in-house mental health counseling capacity, saying student needs have soared.

Added to other challenges for youth are fears about possible school shootings, as well as their anxiety over past, highly publicized violent incidents across the U.S. In all, the vast majority of youth surveyed in the 2023 nationwide poll expressed feeling negative emotions, like anxiety and stress, in connection to gun violence. Gen Z also reports that deep concerns about social, political and environmental issues are taking a negative toll on their mental health. About 2 in 3 youth expressed feeling stress, anxiety and depression tied to hearing about climate change and other environmental impacts.

LGBTQ+ youth are experiencing greater challenges to mental health than their peers, according to NAMI.

At least part of the increases in reported depression and anxiety could stem from something that’s generally seen as positive: Youth are increasingly more aware about their mental health and more open to discussing it than older generations, a sign of fading stigma around the issue.

Not enough mental health providers

A shortage of mental health care professionals statewide is yet another aspect of the youth mental health crisis, particularly in New Mexico. More than 178,000 youth, ages 19 and under, live in 14 counties of Southern New Mexico, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2022 data. Nearly all reside in zones designated by the federal government as Health Professional Shortage Areas for mental health, meaning there aren’t enough providers, like counselors and psychiatrists, to serve the entire population.

What does this mean for Southern New Mexico? While there are mental health providers serving many communities, it sometimes means families have to wait months to have their child seen by a provider unless they’re experiencing an immediate crisis, experts said.

Childhood and adolescent years are key times to have access to mental health care. About half of “all lifetime mental illnesses develop by age 14, and 75% develop by age 24,” according to the NAMI website.

Poverty abounds across the southern half of the state, especially in rural areas, compounding challenges for families and residents to access care, mental health care included. Economic insecurity takes a direct toll on people’s mental health. One counselor said this stress trickles down to kids. In Doña Ana County, the most populous in Southern New Mexico, about one in three children live in poverty, according to New Mexico Voices for Children. Economic insecurity and challenges that go hand in hand with it are among some of the most significant social determinants of health — the non-medical conditions that greatly impact residents’ well-being like whether a person has access to enough food on a regular basis or has a reliable car to get to doctor appointments.

In addition to picking up stress from their parents and caregivers, members of Gen Z report worrying about their own financial futures and abilities to find jobs.

While alcohol and substance use has declined over time among youth, students from the Gadsden Independent School District, located between Las Cruces and El Paso, who spoke with the Southern New Mexico Journalism Collaborative about mental health expressed concerns about drugs and vaping — and the disruptions they cause — in their schools. Some said they can face bullying by other students who do use drugs — and provide them to other students — but who don’t want that information relayed to teachers.

Psychiatric center expanding

A major provider of youth mental health care is the University of New Mexico Children’s Psychiatric Center in Albuquerque. The facility has a psychiatric center, including 35 beds, and focuses on intensive care for children through the age of 17.

“We’re the only center in the state that cares for children with serious emotional disturbances — regardless of a family’s ability to pay,” according to the UNM Health website.

The center gives support to health care providers throughout the state. It’s also constructing a new, 32,500-square-foot facility that will offer 36 beds initially and up to 52 eventually. But reaching the center requires a several-hour drive for families in parts of Southern New Mexico.

UNM focuses on mental health services for Native American youth, who face disparities, such as higher rates of attempted suicide than other groups. Mental health issues have been seen to also affect Indigenous communities when it comes to bullying. Indigenous families in rural areas often have kids that move out of their reservations and pueblos when attending college or looking for work.

Rhoten, of NAMI Southern New Mexico, said she thinks more awareness is needed in schools and among providers about Native American communities and “keeping that cultural sensitivity that is needed for the care.”

“It definitely needs to be acknowledged,” she said. “We are a pretty diverse state, and we shouldn’t be denying cultural things that are not harming anyone else.”

Fostering discussion about mental health

Despite ongoing challenges, a variety of efforts are underway to improve youth mental health. Rhoten said her staff provides peer services to counter many of the mental health challenges students are experiencing. And they work to help parents to better understand the diagnosis of their child. Many parents come from a stigma and grew up in a time when it was frowned upon to seek help for mental health, according to Rhoten.

“We are trying to build a culture where people can talk about it, and it’s a safe place,” she said. “You can learn about it and not be afraid or be ashamed about it.”

A number of schools in Southern New Mexico have either hired a professional mental health therapist or have a school-based health center that offers mental health services. These school-based health centers make mental health care more affordable for students and their families. Southern New Mexico communities with such centers include Anthony, Carlsbad, Chaparral, Clovis, Deming, Hatch, Hobbs, Las Cruces, Roswell, Ruidoso, Santa Teresa, Silver City, Socorro, and Truth or Consequences. Even so, the overall shortage of mental health professionals can hinder access to care in some centers.

Students host suicide awareness effort

In addition to exploring problems, the 2023 nationwide poll on youth mental health uncovered reasons to be hopeful. For instance, about 70% of youth surveyed reported they use some form of mental health support, including self-help practices, therapists, support groups and hotlines. Meanwhile, about 8 in 10 youth said they discussed their emotions or mental health with another person. And many are taking proactive approaches to the social and political issues they care about and are otherwise a source of worry.

That’s the case at Organ Mountain High School in Las Cruces, where students organized an awareness campaign about suicide to help their peers.

Principal Luis Lucero said he created a parent leadership team, a core teacher leadership team, and a student leadership group at the high school. Two members of the student leadership group, which consists of the student body president and members of the student council, suggested hosting an initiative for National Suicide Prevention Week in early September. Lucero, who lost his best friend to suicide about 12 years ago, was quick to agree to the idea.

The students said their goal was to change the narrative of suicide and the importance of speaking about the topic. Lucero said the campaign was relevant to faculty and staff, as well.

“One of the things that came to mind is Hispanic men, Latino men, especially in this area – and I’m one of them – have been taught that it’s weakness to go out and look for help or get counseling,” he said.

Among the ages 10 to 24 group, deaths by suicide were on the rise for about a decade in New Mexico. In 2021, about 20 youth per 100,000 population died by suicide, compared to 14 in 2011, according to state data.

Student body President Abigail Hernandez, a senior, said students’ goal was to encourage conversation about a sensitive, but important, challenge among youth.

“Our end goal was to change the narrative on suicide,” Hernandez said. “Everyone is one social media, which they are very aware of depression and mental health issues, but they don’t necessarily know how to work to better themselves or to get to a better state of mind.”

The nationwide 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline is available by text, call or web chatbox 24-7 year-round for anyone — including youth — experiencing a mental health, emotional or substance abuse concern. People can call the line if they’re worried about someone else’s mental health, too.

Hernandez said that she hopes the student initiative will remain a constant practice at Organ Mountain High School. Lucero said the students are leading the charge and he is “very proud” of them.

Student Council member Lilli Roman encouraged students to seek out help if they need it.

“I’d like for students to know that there is a safe place for them.” Roman added. “They’re scared to go to a counselor or scared to get help but they shouldn’t be because that’s what they are there for.”

Juan Corral is a freelance journalist working with the Southern New Mexico Journalism Collaborative, a partnership of local news organizations in the southern half of the state. SNMJC Editor Diana Alba Soular contributed to this report.